Jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) is the most famous WA tree, noted for its fine timber qualities. With attractive reddish-brown stringybark and a full canopy of bright green foliage, a grove of old, undisturbed jarrah is a beautiful but rare sight. The Jarrah Forest is an Australia bioregion, originally some 50000 km². Remaining stands of old-growth forest is however, much less at around 2500 km² scattered widely over its former range. Jarrah also grow on the Swan Coastal Plain and the Warren region along with marri, for an original total area of around 72500 km² with giant trees scattered widely through out this range. Most old-growth jarrah remains in state forest unprotected from harvesting, and there are no national parks with extensive old-growth forest. Initial attempts 100 years ago to preserve areas as national parks were unsuccessful with the government changing reserves to state forest for timber harvesting! This practice continued for decades until the Forest Department began setting aside small areas for conservation and recreation from the 1960s onwards. Although government promises over the years to ban old-growth logging, legislation has quietly changed terms, and old-growth logging continues despite public protests. Challar Forest was logged in 2014 revealing 400 year old jarrah to be used for firewood and woodchips, creating anger within environmental groups in WA. The tiny remaining patches of old-growth jarrah it seems are too valuable to protect. However in 2022 the government announced plans to halt all old growth logging in Western Australia by 2024. Details are still as yet to be decided and old growth clearing and mining are still allowed but this is great news.

Jarrah was first logged in the 1840s, and it quickly became highly demanded around the British Empire. Some of its appealing qualities are its strength, durability and attractive appearance. Its uses were many, indoor high-quality furniture, general building construction including panelling, flooring and framing. Outdoor uses was extensive with heavy building construction, public works buildings and marine applications including bridges, piers and jetties, as well as fence posts and roads. Across Europe, jarrah blocks were used for roads with asphalt layered on top and also for underground construction for early railways in London, Paris, Berlin and Moscow! It was also shipped extensively across Africa and Asia for railway sleepers and of course as fuel for fires although jarrah is tricky to ignite. Second growth jarrah logs are still used for telegraph poles weighing up to 2 tonnes.

The largest areas with some protection such as Lane Poole Reserve just south of Dwellingup has a lot of great campsites available with at least 10 giant jarrah located there. The two biggest are both sign posted as King Jarrah which was a common practice started many decades ago to indicate to tourists that this is a large jarrah tree! Although only one is accessible by road now as ongoing bauxite mining nearby has closed road access for decades to the other tree. There is however, a scenic walking track to it but it is a day hike, or you can bush bash with a GPS like I do, prickles and all!

Overall there are about 30 giant jarrah listed on the register, only a handful listed are signposted as King Jarrahs however, still standing around the Southwest forests.

Jarrah was first logged in the 1840s, and it quickly became highly demanded around the British Empire. Some of its appealing qualities are its strength, durability and attractive appearance. Its uses were many, indoor high-quality furniture, general building construction including panelling, flooring and framing. Outdoor uses was extensive with heavy building construction, public works buildings and marine applications including bridges, piers and jetties, as well as fence posts and roads. Across Europe, jarrah blocks were used for roads with asphalt layered on top and also for underground construction for early railways in London, Paris, Berlin and Moscow! It was also shipped extensively across Africa and Asia for railway sleepers and of course as fuel for fires although jarrah is tricky to ignite. Second growth jarrah logs are still used for telegraph poles weighing up to 2 tonnes.

The largest areas with some protection such as Lane Poole Reserve just south of Dwellingup has a lot of great campsites available with at least 10 giant jarrah located there. The two biggest are both sign posted as King Jarrah which was a common practice started many decades ago to indicate to tourists that this is a large jarrah tree! Although only one is accessible by road now as ongoing bauxite mining nearby has closed road access for decades to the other tree. There is however, a scenic walking track to it but it is a day hike, or you can bush bash with a GPS like I do, prickles and all!

Overall there are about 30 giant jarrah listed on the register, only a handful listed are signposted as King Jarrahs however, still standing around the Southwest forests.

The above image shows typical jarrah bark. A soft, fibrous stringybark, always growing in the same nearly vertical direction. Younger, newer bark is reddish-brown, compared to the outer, older grey-brown bark. Jarrah grows on laterite soil producing a red gravel appearance and contains high amounts of aluminium ore from its bauxite components. Annual rainfall is between 700-1300mm. The forest ecosystem is complex with jarrah and marri dominating. To the east, wandoo (Eucalyptus wandoo) mix with the drier Jarrah Forest and further south yarri trees inhabit wetter areas of the Jarrah Forest. Around water courses flooded gum (Eucalyptus rudis) and paperbarks (Melaleuca) line rivers and swamps. Smaller understory tree species include sheoak (Casuarina) and banksia (Banksia) which grow throughout the Jarrah Forest. Also covering the entire Jarrah Forest are the ancient cycad (Macrozamia riedlei) and grasstree (Xanthorrhoea preissii) both living relics from Australia's Gondwana past. Many animals live in the Jarrah Forest including mammals such as the rare western quoll (Dasyurus geoffroii), quokka (Setonix brachyurus), quenda (Isoodon obesulus), western brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula), western grey kangaroo (Macropus fuliginosus), various species of micro-bats and WA's native emblem the endangered numbat (Myrmrecobius fasciatus). I once saw an echidna (Tachyglossus acaleatus) on Big Tree Road, named for the Looming Relic. Birdlife includes the endangered Carnaby's black cockatoo, tawny frogmouth (Podargus strigoides), bush stone-curlew (Burhinus grallarius), emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), as well as various types of parrots, fairywrens, honeyeaters, several birds of prey and owls. At the forest floor, insect life recycles the soil adding nutrients.

Due to extensive clearing and land usage, very little jarrah forest has remained or grown back. Initial logging was selective, but second-growth logging was mechanised, clear-felling which often disturbs the soil too much reducing the forests ability to thrive. In many areas, Monterey pine (Pinus radiata) has been planted as jarrah simply couldn't be rehabilitated.

To compound this problem has been the significant issue of dieback, a soil-borne water mould that infects the tree's roots. This causes root rot preventing nutrient absorption leading to the death of the tree, and often spreading to many other trees in the forest. I am careful not to explore forests in winter as wet conditions spread the zoospores. I also carry with me a solution to spray my 4WD tyres and wheel arches and my boots to further reduce to risk of spreading the disease.

In spite of these hardships, the Jarrah Forest continues to endure. The first time I found a noted grove of old-growth jarrah off Kinsella Road was a memorable experience. The light was failing and I thought I would have to give up, but I walked into a grey stand in a quiet section of forest and instantly knew I had found them amongst all the regrowth. These trees were growing near a rocky slope, they were never going to be giants so were never logged. Their trunks were twisted but clean barrelled for 15 metres with heavy limbs and intricate canopy structures.

Due to extensive clearing and land usage, very little jarrah forest has remained or grown back. Initial logging was selective, but second-growth logging was mechanised, clear-felling which often disturbs the soil too much reducing the forests ability to thrive. In many areas, Monterey pine (Pinus radiata) has been planted as jarrah simply couldn't be rehabilitated.

To compound this problem has been the significant issue of dieback, a soil-borne water mould that infects the tree's roots. This causes root rot preventing nutrient absorption leading to the death of the tree, and often spreading to many other trees in the forest. I am careful not to explore forests in winter as wet conditions spread the zoospores. I also carry with me a solution to spray my 4WD tyres and wheel arches and my boots to further reduce to risk of spreading the disease.

In spite of these hardships, the Jarrah Forest continues to endure. The first time I found a noted grove of old-growth jarrah off Kinsella Road was a memorable experience. The light was failing and I thought I would have to give up, but I walked into a grey stand in a quiet section of forest and instantly knew I had found them amongst all the regrowth. These trees were growing near a rocky slope, they were never going to be giants so were never logged. Their trunks were twisted but clean barrelled for 15 metres with heavy limbs and intricate canopy structures.

In the mid 1990s I took my family to the old Hoffman Mill for the Bridges Walk, a short bushwalk around some regrowth jarrah forest but for me, the attraction was a large remnant jarrah tree highlighted, a King Jarrah! On the drive up Logue Brook Dam Road massive felled jarrah logs began lining the road, their red heartwood vivid from recent rains. I'd never seen such a sight. There were dozens of logs 2 metres wide and 10 metres long, some bigger. We were saddened but amazed by the size of these logs. It was on the walk nearing the King Jarrah tree that further disappointment came. It was stumped at 50 cm from the ground, no rot, solid and recently cut with bark intact and sap still oozing around the edges. It was around 2.5 m wide, clearly, it was a magnificent giant. I later enquired about its demise but never got a real explanation, it wasn't supposed to be cut was all that I was told, there was little accountability in those days. Looking back I wish I took some pictures of the biggest logs lining that road, they were all removed a few years later.

I always appreciate the moment I am nearing a giant jarrah knowing how special each one is. There are still a few big ones left. I've measured all of the biggest jarrah on the WA significant tree list, there's just a few smaller ones left on the list I need to measure. People often tell me there’s areas still unexplored, but the Jarrah Forest was thoroughly surveyed. Despite my decades of searching, this is the one species I'm yet to discover a really big one by myself. The closest I've come to is the Murray Jarrah at 73 m³ in volume, a giant I initially thought I'd discovered. The nearby and now fallen Amphion Jarrah at 70.8 m³ in volume, had more points so was the champion in that area. The Murray Jarrah I believe had the second most points so was not on the published list. I randomly parked next to it to measure the Amphion Jarrah. When I returned I thought I better measure it and it turned out bigger! I couldn't believe how easy it was to discover giant jarrah. I then noticed the large spray painted 'H' on its base, indicating this was marked as a protected habitat tree, like other large trees in the Jarrah Forest, so its size was already recorded.

I've found around 10 jarrah relics (half alive) which would've had more than 50 m³ in volume once, and several more that would've had more than 60 m³ in volume once. I've also measured around 20 giants 3 m in DBH, mostly around the Perth Hills. These Perth Hills jarrah seem to have bigger bases than others further south, yet don't get the rainfall to become real giants, with shorter trunks than jarrah beginning from Dwellingup south. Most have been damaged and burnt from repeated fires, which, unfortunately is a hazard in the hot summer months. Overall I've measured close to 50 jarrah over 50 m³ in total volume since 2012. The hunt goes on!

Historical Accounts

There are hundreds of historic jarrah images depicting life around the mill of the early settlers and later of the logging era. Very few large jarrah trees are recorded however. The image below is by far the biggest historic jarrah tree I have seen. Known as the Holyoake King Jarrah, it grew in the small town of Holyoake, a few kms east of Dwellingup. I believe it was protected as a tourist attraction but did not survive the major bushfire around Dwellingup in 1961. The town of Holyoake was not rebuilt but no lives were lost. To estimate its total volume, I multiplied estimated volume at 10 m by 2.1. This is the average ratio difference for the biggest Dwellingup jarrahs at 10 m compared to total volume. I've done this on other historic trees, I believe it is the best method to estimate volume from just one image. This is of course assuming that image shows most of the lower trunk and ideally a person for scale, which most do. Many years ago I visited the state library and saw many images of what I would consider as giant jarrah. Those images are still only viewable at the library at this stage. Some are likely of current giants still with us, but were photographed when they were first discovered. Another trip to the state library may be in order to show the biggest giants of the past I can find.

I always appreciate the moment I am nearing a giant jarrah knowing how special each one is. There are still a few big ones left. I've measured all of the biggest jarrah on the WA significant tree list, there's just a few smaller ones left on the list I need to measure. People often tell me there’s areas still unexplored, but the Jarrah Forest was thoroughly surveyed. Despite my decades of searching, this is the one species I'm yet to discover a really big one by myself. The closest I've come to is the Murray Jarrah at 73 m³ in volume, a giant I initially thought I'd discovered. The nearby and now fallen Amphion Jarrah at 70.8 m³ in volume, had more points so was the champion in that area. The Murray Jarrah I believe had the second most points so was not on the published list. I randomly parked next to it to measure the Amphion Jarrah. When I returned I thought I better measure it and it turned out bigger! I couldn't believe how easy it was to discover giant jarrah. I then noticed the large spray painted 'H' on its base, indicating this was marked as a protected habitat tree, like other large trees in the Jarrah Forest, so its size was already recorded.

I've found around 10 jarrah relics (half alive) which would've had more than 50 m³ in volume once, and several more that would've had more than 60 m³ in volume once. I've also measured around 20 giants 3 m in DBH, mostly around the Perth Hills. These Perth Hills jarrah seem to have bigger bases than others further south, yet don't get the rainfall to become real giants, with shorter trunks than jarrah beginning from Dwellingup south. Most have been damaged and burnt from repeated fires, which, unfortunately is a hazard in the hot summer months. Overall I've measured close to 50 jarrah over 50 m³ in total volume since 2012. The hunt goes on!

Historical Accounts

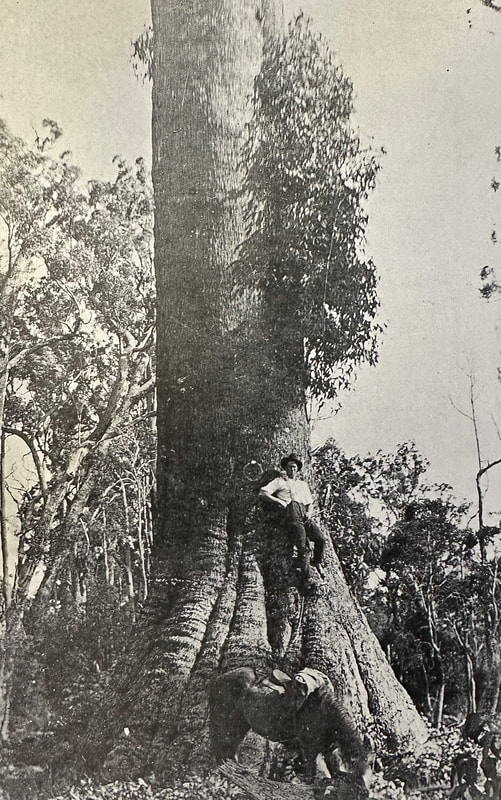

There are hundreds of historic jarrah images depicting life around the mill of the early settlers and later of the logging era. Very few large jarrah trees are recorded however. The image below is by far the biggest historic jarrah tree I have seen. Known as the Holyoake King Jarrah, it grew in the small town of Holyoake, a few kms east of Dwellingup. I believe it was protected as a tourist attraction but did not survive the major bushfire around Dwellingup in 1961. The town of Holyoake was not rebuilt but no lives were lost. To estimate its total volume, I multiplied estimated volume at 10 m by 2.1. This is the average ratio difference for the biggest Dwellingup jarrahs at 10 m compared to total volume. I've done this on other historic trees, I believe it is the best method to estimate volume from just one image. This is of course assuming that image shows most of the lower trunk and ideally a person for scale, which most do. Many years ago I visited the state library and saw many images of what I would consider as giant jarrah. Those images are still only viewable at the library at this stage. Some are likely of current giants still with us, but were photographed when they were first discovered. Another trip to the state library may be in order to show the biggest giants of the past I can find.

This image of the Holyoake King Jarrah is from 1919, near the town of Dwellingup, it looks more like a red tingle! A tree hunting friend of mine Kim sent me this image. Apparently it was a popular post card in the Dwellingup visitor centre, but by the 1990s was no longer sold. I estimate the diameter at BH at 4 m with a base width of 5 m! Estimated total volume is about 122 m³, going with a volume at 10 m of 58 m³. Width at 10 m is about 1.8 m. By 3 m our current champ, the Looming Relic is wider but both trees are exactly the same volume! Image is reproduced with permission from the State Library of Western Australia.

This image of the Nannup Jarrah is from 2012. This was a previous top ten jarrah on the list below. I visited it again in 2022 to find it had fallen probably a few years earlier. It was 2.7 m in DBH and 78.3 m³ in total volume and one of the first really large jarrah trees I saw. It's the second biggest historic jarrah I know of, assuming the Holyoke King Jarrah had a full trunk and canopy. A fallen king jarrah 50 metres from the giant King Karri near Donnelly River Village was 2.7 m in DBH and likely around the 80 m³ in total volume when I saw it in 2020.